DESCRIPTION

Description of the works by Chen Fei

2nd floor

-

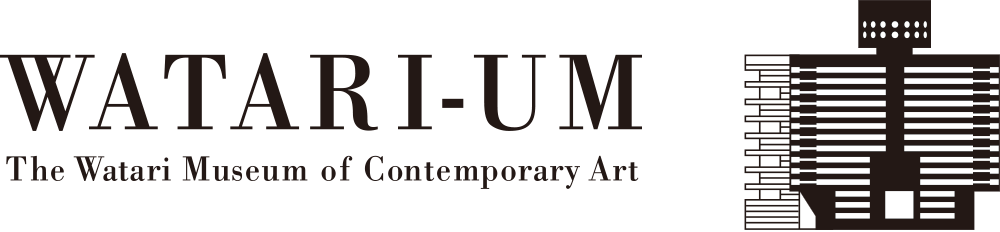

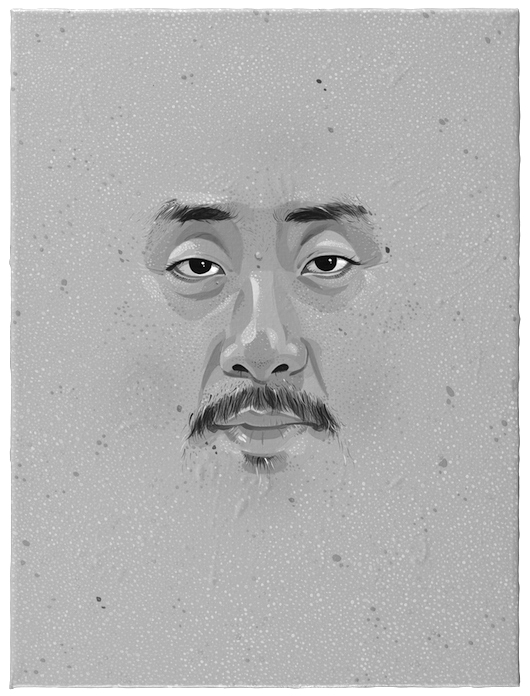

- Some People

- 2025

-

Acrylic on linen 50 × 40 cm

Some People depicts my father and myself. Though modest in size, it took me years to complete—often left unfinished, pushed aside, then revisited. I’ve always seen myself as a realist, a figurative painter, and that very position can become a limitation: it holds one close to the world, to its frictions, its unease, its disappointments. Over time, what emerged was a sense of silent futility. The figure in the background, my father, is rendered in the style of a bureaucratic headshot: a format that immediately recalls power, hierarchy, and control. This paternal and systemic presence looms quietly from behind, exerting a form of invisible control. Through a personal, domestic image, I allude to a broader mechanism of intervention and constraint, one that weighs on us all.

-

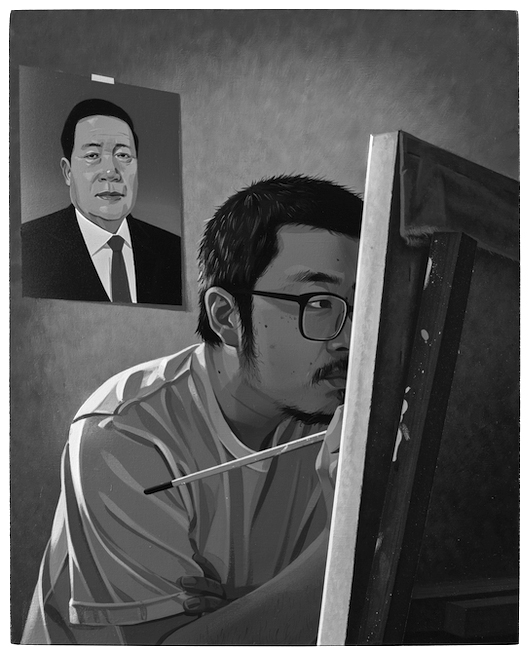

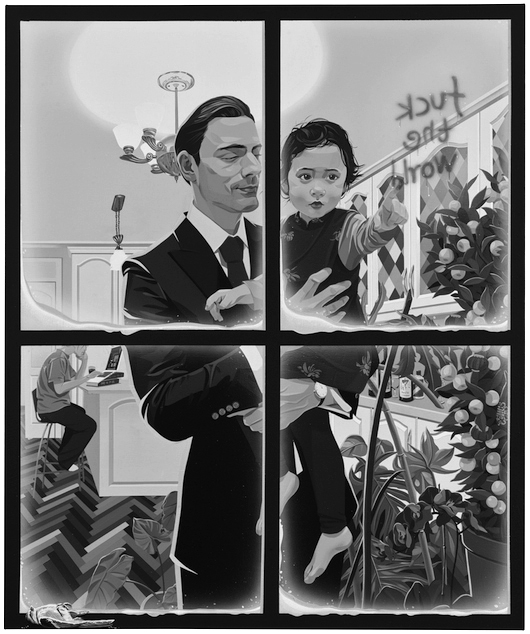

- Biotheatricality

- 2025

-

Acrylic on linen 150 × 270 cm

The more mundane the scene, the more intricately I want to compose it. I wanted to view the depicted content as if I were looking at it from outside the screen. For example, if I could observe scenes repeated in everyday life from the standpoint of an outsider or from the perspective of a different species, such as through the compound eyes of a fly: Can other creatures feel human joy, anger, sorrow, and pleasure?

During the creative process, I first drew the people in a single frame, then copied it over and over again to test my limits. I wondered if I could draw everything the same way. This is “play” for me, and it simultaneously reflects the repetitive human behavior as seen through the compound eyes.

-

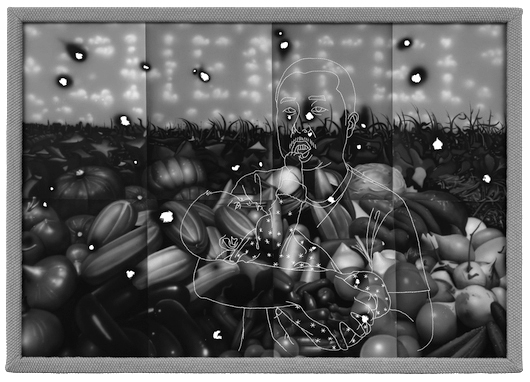

- Abundance

- 2022

-

Linen, acrylic, wood frame, yarn, mixed media 150 × 210 cm

Abundance and Biotheatricality mark a shift in formal approach—through the use of mixed media, or through the adoption of non-rectangular formats—as a way of reflecting multiplicity. As I’ve long believed, painting carries its own modes of legibility. Not every image lends itself to narrative progression or moral clarity. At times, what matters more is the space left open: for speculation, for imagination, even for misreading. I hope these works might offer such a possibility.

-

- Endearment

- 2024

-

Acrylic on linen 70 × 80 cm

Endearment serves as a quiet counterpart to Love Sonnets. While the latter leans toward surface and pattern, this painting was conceived as a fragment of the real—a modest, almost theatrical corner of the everyday. What it presents may cause slight discomfort, yet like a moment of tension in a play, it appears without warning and simply stays, whether we meet its gaze or not.

-

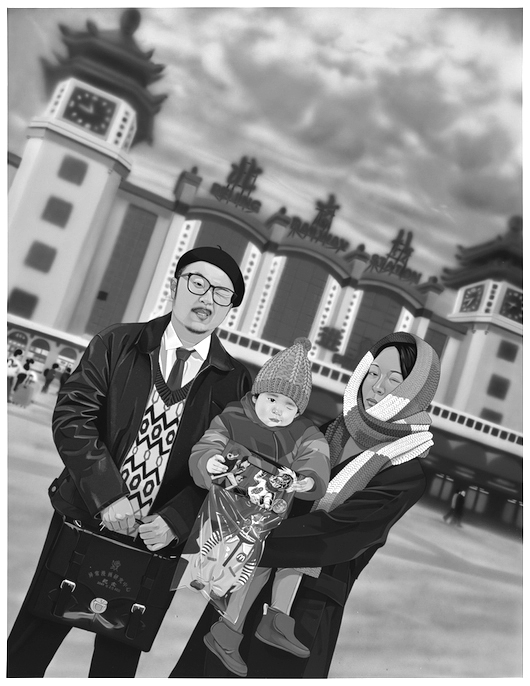

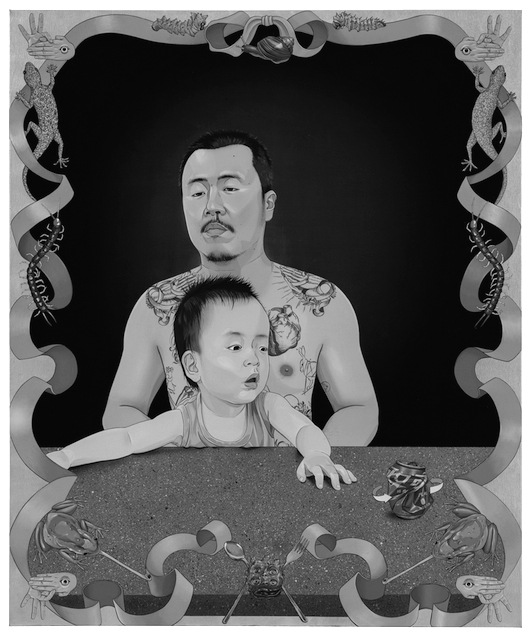

- Cartoonist's Voyage

- 2024

-

Acrylic on linen 290 × 220 cm

I had the impression that nearly every Chinese family of my generation owned a photograph like this. But after combing through my parents’ albums, I found none. That sense of familiarity, I came to realize, stemmed not from lived experience, but from a visual archetype—one so pervasive it had displaced memory itself. So I decided to create one of my own. I set it in the future—a future not necessarily shaped by progress, but just as likely by recursion. A cartoonist, traveling on state assignment, takes the opportunity to bring his family along. In a world defined by uncertain ideology, perhaps little can be done. But at the very least, one might still make a face at it.

-

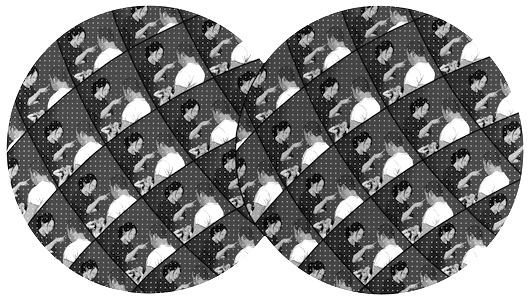

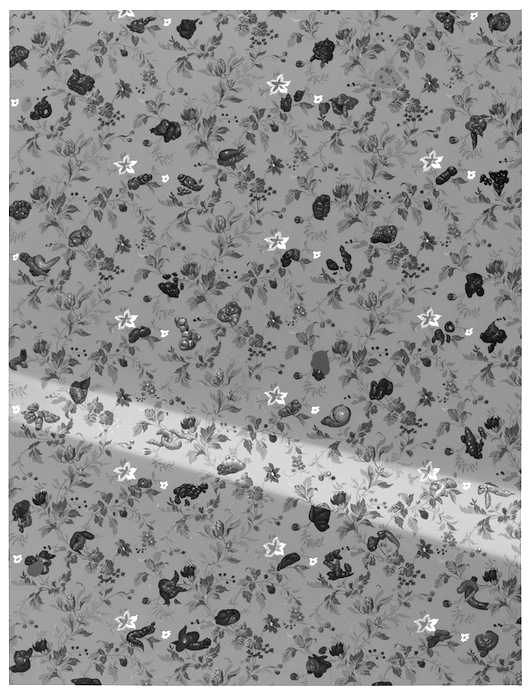

- Love Sonnets

- 2024

-

Acrylic on linen 290 × 220 cm

This painting begins with a memory. My daughter was born prematurely, weighing just under two pounds. Frail from the start, she required constant care. And one of my unexpected daily duties as a new father was tracking her bowel movements. In both Chinese and Western medicine, an infant’s stool is an important sign of health, so photographing her diapers became part of my daily routine. Years passed, and as she grew stronger, I left that chapter behind. It wasn't until I was scrolling through my phone for something else that I stumbled across that forgotten archive—hundreds of diaper photos, each showing a different form and color. They seemed almost like a language. Before my daughter could speak, perhaps she was already saying: “Daddy, I’m fine today. Look how perfect the shape is,” or “Daddy, I’m not feeling so well... the color’s a little off.” I didn’t recoil. Instead, I felt a quiet tenderness. Looking at them all together, it felt less like documentation and more like a long poem. I’m well aware this is a father’s gaze—what touches me may not move anyone else. But I still felt an irresistible need to give it form. As a painter, I couldn’t bring myself to render such residue literally. So I turned instead to the language of Neoclassicism, and to the way William Morris arranged forms across surface—reconfiguring the images like wallpaper, flattened and ornamented. That felt like the most fitting approach. A single beam of light cuts through the surface, breathing air into a composition saturated with form. This is, undeniably, a deeply personal painting. But then again, isn’t that why I became a painter in the first place—to please myself, before anyone else?

3rd floor

-

- Fruits of Bloom

- 2025

-

Acrylic on linen 40 × 30 cm

-

- Roommate

- 2023

-

Acrylic on linen,mixed media 200 × 260 cm

I have long been interested in the format of identification photographs—those required for passports, student IDs, work permits, marriage certificates, even funerals. They differ in color, size, and dress code, yet all serve the same purpose: to validate one’s identity in relation to a specific role. How is it, I wonder, that such compact representations can so readily define who we are, and fix us in relation to others?

Roommate began as an invented wedding photo, enlarged to an exaggerated scale. What was initially conceived as a subtle gesture of irony soon evolved into a question of form. Once the figure surpassed human proportion, it could no longer be handled as a portrait. It became something else—an architecture of sorts. Composition, surface, and volume began to take precedence over narrative. The subject receded, and with it, the premise I had set for myself quietly fell away. What remained was the act of construction: how to resolve a transition, how to weight a shadow. In the end, I painted not a likeness, but something closer to a building.

-

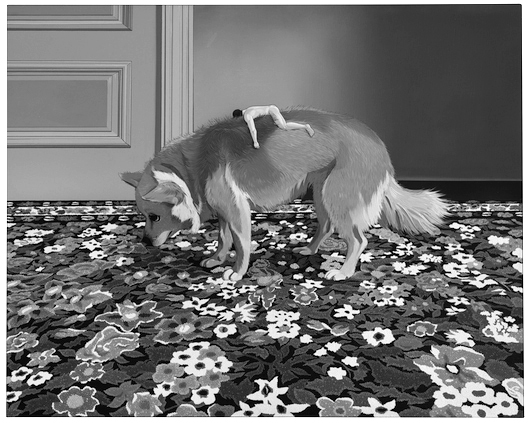

- Old Soul

- 2023

-

Acrylic on linen 80 × 100 cm

During a visit to the Palace Museum in Beijing, I came across a Qing dynasty imperial portrait. It wasn’t the figure that drew me in, but a section of the carpet beneath it. Though executed in the tradition of gongbi, the treatment of the carpet resembled something closer to Seurat’s pointillism—evoking a dense, tactile materiality I had never encountered in ink-based painting. One could begin to suspect that the presence of Western painters in the imperial workshop predates what history typically affirms. It is not a question I can resolve, yet it continues to return. Somewhere else, another thread had long been left open. Years ago, I began painting my dog, who had been with me for eighteen years—but halfway through, I stopped. It felt like an ill omen, as if completing the work might hasten her departure. The canvas remained unfinished. After she was gone, it stayed that way for a long time. After the encounter at the Palace Museum, the memory of that painting returned. I realized I could now complete it—calmly, without hesitation. This time, feeling was accompanied by thought; intuition and judgment moved together, sometimes in friction. I turned to acrylic, hoping to find a material clarity that might approximate what felt right. Old Soul emerged from that convergence.

4th floor

-

- Still Life

- 2024

-

Acrylic on linen 40 × 30 cm

Still Life takes the guise of a small portrait, yet operates as an ongoing study of spatial tension. The face presses outward, dissolving the edge of the canvas—not framed, but diffused—contemplating its own expansion.

-

- What follows is a group of five paintings, identical in size and held in a steady visual register. Together, they articulate the central formal proposition of “Father and Child.”

-

- Holiday

- 2025

-

Acrylic on linen 120 × 100 cm

Holiday is a more private work. The central figure is my longtime friend, with whom I’ve shared a quiet, enduring rapport. His family structure is the same as mine. Observing others has always been central to my practice. In them, I see both what I’ve lived and what I haven’t—formations, dissolutions, arrivals, partings. Their experiences resonate with me, and often feel strangely proximate. This painting began with that impulse: to see another father, and in doing so, to return to “Father and Child” from a different vantage.

-

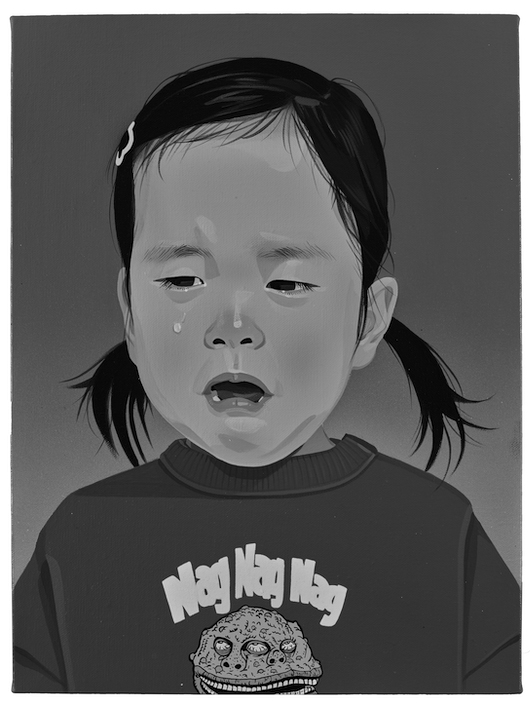

- Supernatural

- 2022

-

Acrylic on linen, gold foil 120 × 100 cm

Supernatural is the first painting I made of my daughter—not as a study or gesture, but as a complete work. The structure was already there: composition, symbolism, formal decisions I had long internalized. But once the painting began, I found myself unprepared for its simplest demand. Much like becoming a father, it brought on an unexpected tension. I became anxious not about the image as a whole, but about her—whether the likeness held, whether she looked “right.” Concerns that should have stayed peripheral came forward, unsettling the balance. In the past, I knew how to tolerate a painting’s failure. My training had taught me that unfinished work could be set aside, reworked, or discarded altogether—given time, something would eventually resolve. But this painting didn’t follow that logic. It felt as if the painting had begun to lead, not follow. Perhaps it was because of the child—because I cared more, or because my attention to her began to eclipse everything else I had once held central. I tried to deny that her arrival might shift my work, told myself that practice should remain indifferent to circumstance. But the change came slowly, then steadily, and eventually I allowed that feeling might be reason enough. But in the end, that shift had to be resolved through painting itself. As the work developed, I made certain formal adjustments—introducing peripheral imagery to counterbalance my fixation on the central figure, and to open a space for projection. Conceptually, I wanted to hold a single instant still, while suggesting movement beneath its surface. The scene became a kind of visual game, borrowing from my college training in storyboarding: each gesture imagined as part of an unseen sequence, suspended yet in motion.

-

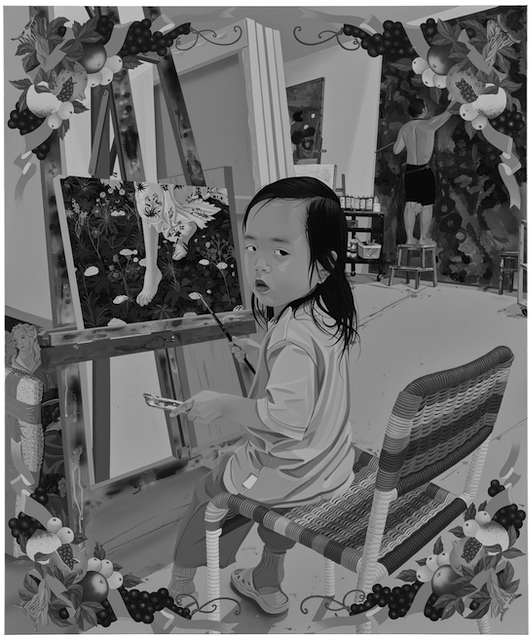

- A Craftman Father

- 2025

-

Acrylic on linen 120 × 100 cm

A craftsman father reflects the overlap between the domestic and the studio, where life and work unfold in the same space. Here, roles are inverted: the daughter effortlessly brings Botticelli’s Primavera to life, while the father, in the background, is still caught in the struggle to become the abstract painter he once imagined. For all his doubts about figuration, what he cannot escape is this: it isn’t the style that matters, but whether the painting can be felt.

-

- 2025

-

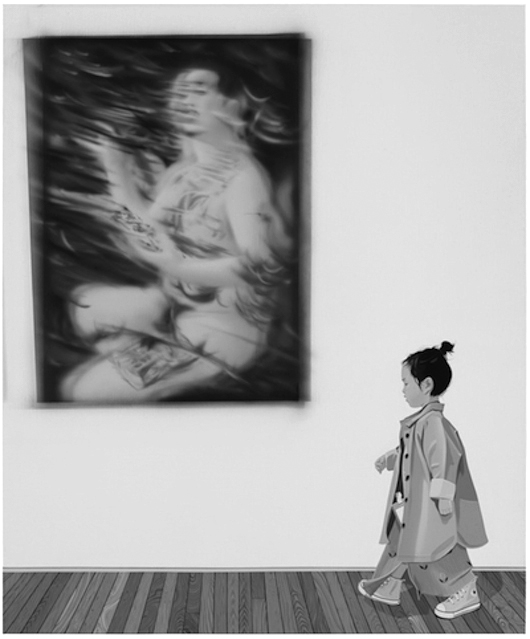

Acrylic on linen 120 × 100 cm

PDF plays with a recognizable staging convention: an artwork hung against a pristine white wall, a blurred figure passing by. Once meant to suggest scale and spatial context, this trope became shorthand within contemporary display language, projecting a sense of clarity and polish. Over time, it spread: across major institutions and independent spaces alike, until the gesture turned habitual. I found the repetition quietly absurd. So I reversed it—the figure is rendered in full clarity, while the artwork dissolves into blur.

-

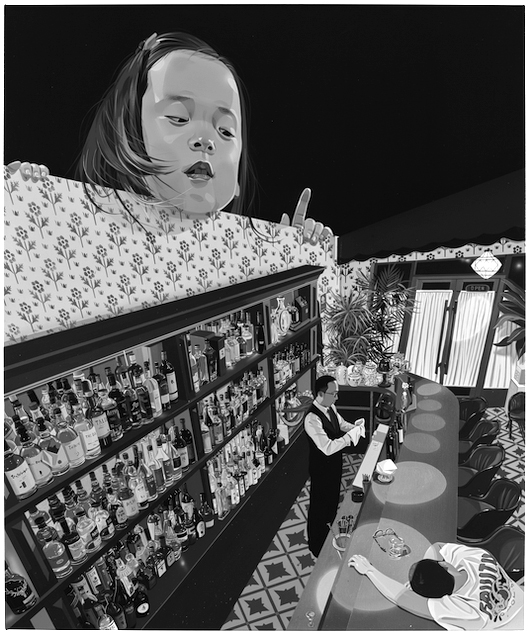

- Father's Lament

- 2025

-

Acrylic on linen 120 × 100 cm

Father’s Lament assumes the structure of a staged tableau. At the threshold of a spatial fiction drawn from everyday theatre, a child, much like a displaced Alice, hovers in partial view. She watches from above, half perplexed, half amused, as the world of adults performs its routines.